these Walls Have a Story to Tell

Self Guided Tours

Wednesday – Sunday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

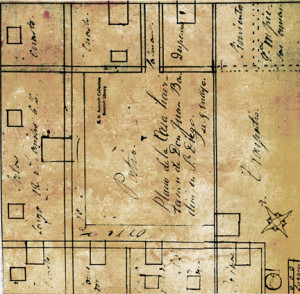

Imagine Old Town San Diego in the 1830s – no trees, no grass, no wooden buildings – just a handful of adobe homes scattered around a dry, dusty plaza. Between 1827 and 1829, Juan Bandini had a “U” shaped family home built off one corner of the plaza. Compared to most of the other modest adobes, Casa de Bandini was a “grand mansion,” bringing vibrancy to life in old San Diego. The rooms had thick, insulating adobe walls. The ceilings were covered on the inside with heavy muslin to trap insects, dirt, and straw that fell from the thatch roof.

Construction of the casa was a colossal undertaking. The building contains as estimated 10,000 adobes bricks, weighing as much as 60 pounds each. The foundation, made of large round river rocks, rose four and one half feet above ground at the corner facing the plaza. The heavy labor was most likely performed by Christianized Indians hired from the local mission.

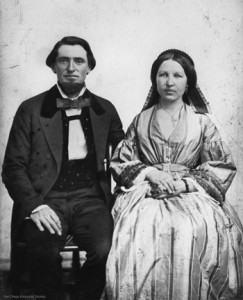

Don Juan Bandini typified the grace, grandeur, and dignity of the Mexican Californio culture of time. Cattle ranching was the economic cornerstone of San Diego during the 1830s and 1840s, an industry that made Bandini and the few other ranch owners quite wealthy. He also held a variety of public offices. Ever dissatisfied with whatever government he lived under, Bandini even planned the occasional government overthrow in his home. On one such occasion, Bandini and his San Diego accomplices took up arms, went to Los Angeles, deposed the governor by force, sent him packing on a ship bound for Mexico, and placed one of their own on the governor’s chair. Back in the good old days!

Bandini’s three daughters from his first marriage — Josefa, Arcadia, and Ysidora — were fabled to be the most beautiful women in California. The youngest, Ysidora, fell from the balcony of their home into the arms of American, Lieutenant Cave Couts, while he was on horseback – or so the legend goes (if you’re paying attention, you’ll note that there was no balcony on Casa de Bandini when this event took place! But grand realities lead to even grander tales). Even today, Ysidora’s ghost is thought to visit room 11 at The Cosmopolitan Hotel, turning lights on and off and engaging in other spritely mischief.

Bandini was known for his elegant dress and gracious demeanor. He was said to be a charming public speaker, fluent writer, fair musician, and fine horseman. However, Juan Bandini and his home are most fondly remembered for hosting grand week-long fandangos (dance parties) that cost thousands of dollars! Their home was the social center of town. Bandini was a consummate dancer. He loved dancing so much that he had the first wood floor in San Diego. It is thought that the first time the waltz was ever danced in the state of California, was on Bandini’s wood floor in the early 1830s. Richard Henry Dana, Jr., an American who visited San Diego in the 1830s, wrote in Two Years Before the Mast, “Bandini…gave us the most graceful dancing that I had ever seen. His slight and graceful figure was well calculated for dancing, and he moved about with the grace and daintiness of a young fawn. An occasional touch of the toe to the ground seemed all that was necessary to give him a long interval of motion in the air. He was loudly and repeatedly applauded, the old men and women jumping out of their seats in admiration, and the young people waving their hats and handkerchiefs.”

But, all good things come to an end…

After the United States wrested control of California from Mexico in the 1840s, many Californios struggled to adapt to the rapid and dramatic shift from a Mexican cattle ranching economy to an American merchant-based economy, and Juan Bandini was no exception. Throughout the 1850s his wealth and health faded. In 1859 he sold his beloved home in an effort to pay off debts, and died just months thereafter.

The grand adobe casa was without occupants by 1860. In 1862 a flood and an earthquake destroyed a wing of the building; it was never rebuilt. Floods, droughts, and neglect during the 1860s caused the building to fall into severe disrepair. However, the building would soon return to glory!

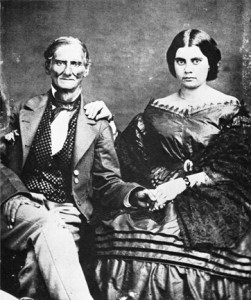

In 1869, American stagecoach operator, Albert Seeley purchased the dilapidated fixer-upper for $2,000 in gold coin. His wife, Emily, had recently inherited $8,000, which was used to build a second story, modeled in a Greek revival theme, and operated it as the Cosmopolitan Hotel. Without Emily’s inheritance money, the Seeley’s probably wouldn’t have purchased and refurbished the adobe, and it would have fallen into ruin, never to be enjoyed again. Thank you Emily!

The second story was well constructed, but not actually attached to the lower adobe level – it just rested on top of the adobe walls! The Seeleys also enlarged the downstairs parlor in order to serve meals and to provide a gathering place for guests. The building featured a saloon, sitting room, billiard room, barber shop, post office, and stagecoach stop. The hotel’s main attraction was its balcony that wrapped around the second story, a grandstand from which guests enjoyed watching a variety of amusements on the plaza, such as 4th of July celebrations, mule team races, circuses, and even bull and bear fights!

By the early 1870s, Albert and Emily’s social standing rose and the building once again became the social center of town. The room was the scene of galas, balls, dances, raffles, family reunions, and weddings. Imagine bellying up to the bar, sipping the choicest wines and liquors, and puffing on a fine Havana cigar (which you paid a mere 20 cents for!). The Cosmo bar even offered lager beer, which requires refrigeration. (Yes, they managed to get a hold of ice and kept it from melting, but we’ll leave that feat to your imagination!). The Seeley’s claimed to spare no pain to make guests feel comfortable. However, Seeley was a bit of a false advertiser – he advertised the Cosmopolitan as a “first-class” hotel, even though it had no gas lighting, running water, or suites, which other first class hotels of the time period did. In any case, during Cosmo’s hey-day, this was the place to be!

But, all good things come to an end…

Eventually, the Seeley’s era of glory faded. As the railroads spread, Seeley’s stagecoach operation gradually became obsolete. Simultaneously, Old Town experienced one of its many economic slumps and the hotel businesses declined – by 1882, it was without a guest. A tragic fire on the opposite side of the plaza sealed Old Town’s fate. The social, political, and cultural center of San Diego shifted from Old Town to the newly establish New Town (The Gaslamp Quarter of today’s downtown). Seeley sold the building in 1888, and it once again fell into disrepair.

Some of the owners during the 20th century put their own touch of style on the face of the building, and many were inspired by rather romantic imaginings of days gone by. Despite multiple alterations and major remodels, it retained roughly 80% of its 19th century structure, hidden beneath layers of 20th century stucco and decorative tile.

In the 21st century, Cosmo has returned to glory again, thanks to a three-year, multi-million dollar restoration project, overseen by the state of California and the hotel’s new proprietor, Chuck Ross of Old Town Family Hospitality Corp. The restoration returned Cosmo to its 1870s splendor! Throughout the building you can see historic reproduction furnishings, American-made antiques from the 1860s and 1870s, as well as a significant amount of original structure including floorboards, wainscoting, widows, window and door frames, and in one room you can still see a bit of Don Juan’s original adobe peaking though.

The Cosmopolitan is one of the most important buildings in all of California; a Mexican adobe lower level, an American wood-framed upper level, and the home and work place of people of diverse ethnicities. Cosmo is a cultural mosaic. Recently, Cosmo has become the social center of town for the third time; join us in celebrating Cosmo’s return to glory!